The use of alternative funding programs (AFP) has been on the rise in recent years, in keeping with the growing number of self-funded employer health plans. Run by for-profit vendors, AFPs are a relatively new type of specialty carve-out program meant to save employers money by removing certain high-cost medications from their formularies.

Instead of filing with their health plan, AFP vendors encourage patients to apply for financial assistance through pharma patient assistance programs (PAPs) or charities. AFPs have serious consequences for pharma companies, as they rapidly deplete PAP funds intended for uninsured patients. (For more on this subject, see my post on how the use of AFPs and specialty benefit managers impacts PAPs—and how pharma companies can proactively counter these effects.)

As I wrote in my first post on AFPs in February 2024, most payers are not in favor of these programs, due in large part to concerns about how AFPs might distort their cost-sharing incentives and limit their control over expensive drugs.

Let’s take a look at our more recent employer and payer research on this topic, conducted in April 2025 on behalf of Fierce Healthcare, for inclusion in an excellent article on the prevalence and dangers of AFPs.

Employer Cite Care Disruptions, Ethical Concerns with AFPs

According to MMIT research, more than half of surveyed employers were aware of the prevalence of various AFPs. Of these employers, 93% were previously approached by an AFP for a potential partnership, but chose not to use their services.

Most employers said they didn’t move forward with an AFP due to concerns about the ability of these firms to execute their services without interrupting care. As one director of Employee Benefits said, “My organization decided not to utilize the services of an AFP organization because we had a concern about the length of time it could take for an employee’s specialty medication request to receive approval and funding for that medication.”

Several employers noted the “ethical and optical concerns” of using AFPs, from forcing patients to apply to another source for funding to the intrusiveness of soliciting personal details for qualification purposes to the misaligned incentives. As one PBM wrote, “My concern is only in ethics. These organizations ‘split the savings’ with the employers so they have the incentive to advise the plan sponsors to not cover products.”

A few employers mentioned that the timing wasn’t right for them to use an AFP, but they would consider this option later on. Almost half of employers said oncology indications were the most common carve-out for AFPs, followed by obesity and diabetes.

Most Payers Avoid AFPs, but Acknowledge Their Growing Footprint

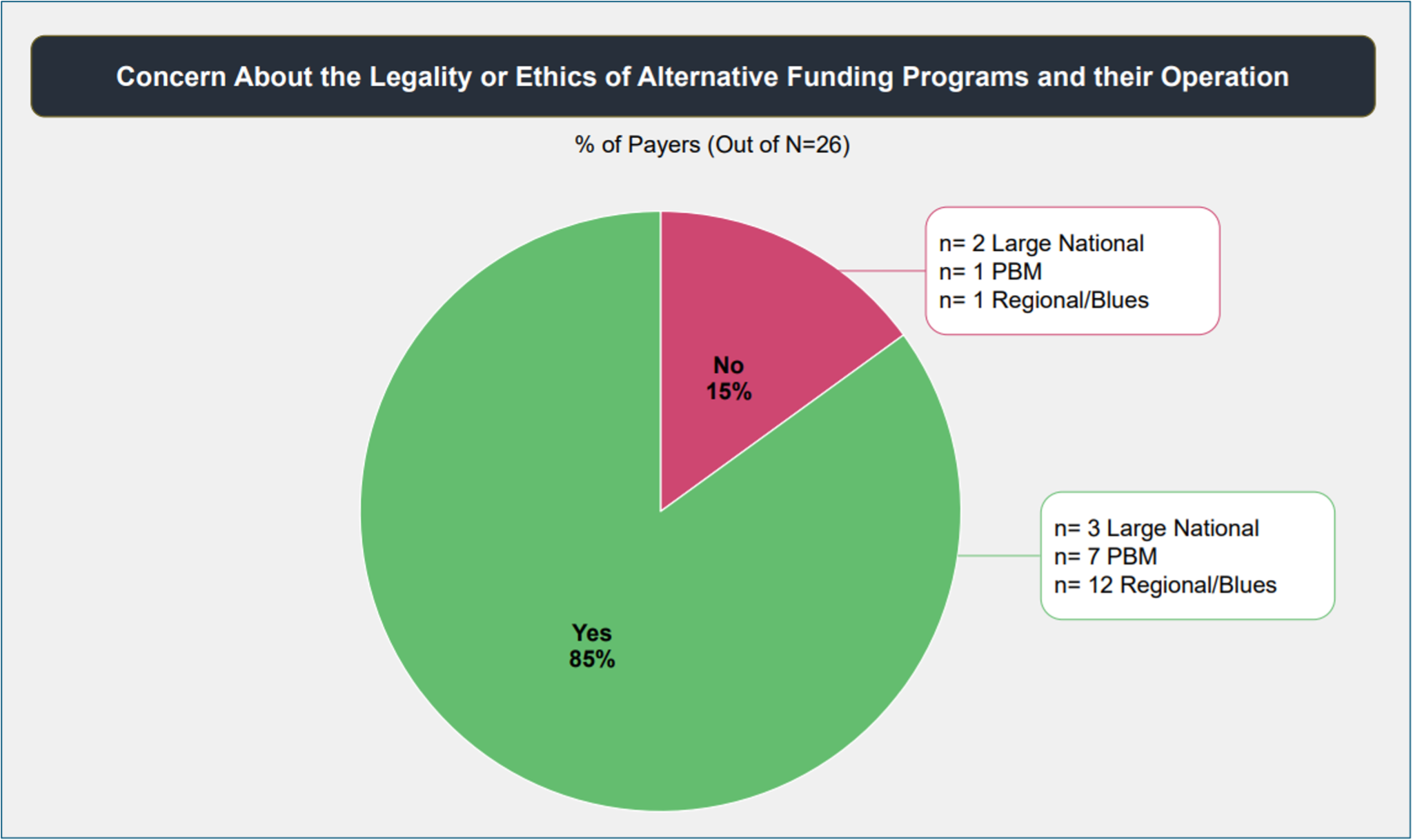

Of the 26 payers and PBMs surveyed by MMIT, 85% reported that they do not contract with any AFPs at this time. However, 58% said they are aware of carve-outs for certain medications by employers using AFPs.

Several large national payers and regional/Blues affiliates mentioned oncology, immunology, and rare diseases as the most common indications for carve-outs, along with high-cost specialty drugs like gene therapies and CAR-T therapies. Multiple PBMs commented on employers seeking carve-outs for orphan, ultra orphan and rare diseases, along with GLP-1s for weight loss “and in some instances, all specialty drugs.”

Of the 15% of surveyed employers who do contract with AFPs, half said they receive no direct benefits from these programs, but these partnerships help to maintain client relationships. According to one large payer, AFPs “reduce drug costs for patients and our plan sponsors,” which in turn “benefits us when these plan sponsors are considering renewal of our contracts.”

The most enthusiastic response was from a PBM representative, who wrote, “the cost savings is significant and realized. The cost of rare disease specialty medications continues to skyrocket and there are minimal rebates to be negotiated. There is little else we can do to save plans money on these therapies. [AFPs] allows these dollars to be used to help bring both plan savings and member savings (one way or another). We also review these clinically via PA to ensure appropriate utilization.”

Payers Say Specialty Carve-Outs Shift Costs, Complicate Rebates

Approximately one-quarter of surveyed payers/PBMs reported that AFPs affect their rebate contracts, drug formulary, and overall cost structure. As one large national payer commented, “AFPs impact our organization by taking members off our drug formulary, which can disrupt care and make it harder to manage treatments. They also reduce the number of claims we process, which can hurt our rebate contracts. While they may seem to lower costs, they often just shift costs elsewhere and create more work and delays for patients.”

One PBM noted the artificial effect of AFPs on rebates, as “higher cost, and higher rebated products are carved out by the AFP, resulting in higher rebate guarantees being paid out for remaining drugs vs. actual, earned rebate amounts.” Regional affiliates said AFPs “shift utilization and preferred agents away from our formulary,” and noted that they can cause “delays in treatment and [higher] out-of-pocket costs for members.”

Overall, 85% of payers reported concerns about the legality and ethics of AFP operations. Many talked about the implications for manufacturer assistance programs, and said AFPs should not be misusing funds meant for people truly in need. As one regional affiliate said, “The program is being used perversely to achieve unintended goals, potentially hurting intended recipients as there are finite resources appropriated to these [patient assistance] programs.”

Other payers expressed concern about the impact of AFPs on their own organization. “They subvert the contractual cost sharing incentives for our membership,” said one regional affiliate. Many agreed that AFPs can unduly influence formulary considerations; as one PBM noted, “there can be unethical levels of influence to drive inclusion or exclusion of certain drugs.”

Few Safeguards Yet in Place to Curb AFPs’ Influence

Despite these widespread concerns, only 35% of surveyed payers have erected barriers to prevent or regulate AFP participation in their plans. Of this group, the majority simply refuse to work with AFPs, while almost half limit eligibility of AFPs to very specific patient populations and/or indications. A handful require prior authorization for medications covered by AFPs, or charge higher administrative fees for handling prescriptions covered by AFPs.

Many pharma companies have taken to legal channels in their efforts to combat AFPs. Companies like AbbVie, Johnson & Johnson, and Gilead Sciences have filed lawsuits against AFPs for fraudulent practices. And several manufacturers have implemented various changes to help prevent AFPs from raiding their PAP funds, from changing patient eligibility requirements to adjusting their federal poverty level screening criteria.

Promoting greater awareness of how AFPs operate may be pharma’s next move. By educating physicians and patients about the existence of AFPs, manufacturers can inform them of the risks. Patients should know that their health insurance plan would not ask all the additional questions AFPs ask before providing access to their medication.

Increasing awareness can undermine AFP adoption over time, as patients can refuse to participate and push their health plan administrators to provide legitimate access to their medication. If patients and physicians protest that AFPs are delaying care, that negative feedback (through patient advocacy groups, HR representatives, professional physician associations) might eventually pressure employers to stop working with AFPs, despite any cost savings.

Gain actionable insights on the questions that matter most to your organization via our Custom Market Research solution, which provides direct feedback from payers, IDNs, physicians and EBMs.